Extreme heat, drought, wildfires. Unfortunately, summer 2022 has been an eye-opening season for many people. As the effects of global warming become more concrete and severe every day, we might finally see some collective actions taking place. However, it is too late to avoid all the consequences and we already know who is going to pay the highest price. Climate change will disproportionately affect socially and geographically disadvantaged people – including people facing discrimination based on gender, age, race, class, caste, indigeneity and disability. The acknowledgement of these inequalities contributed to the creation of the climate justice movement.

Cross-country inequality

The most evident and documented issue concerns cross-country inequality. This term refers to the disproportionate distribution of responsibilities and effects of climate change between countries. Historically, developed countries have contributed most to climate change. To date, 25% of cumulative greenhouse gas emissions came from the United States, 22% from the EU, 13% from China and 3% from India. Today the poorest countries, which make up 60% of the world population, emit only 15% of global CO2 emissions. However, they will suffer the most serious consequences.

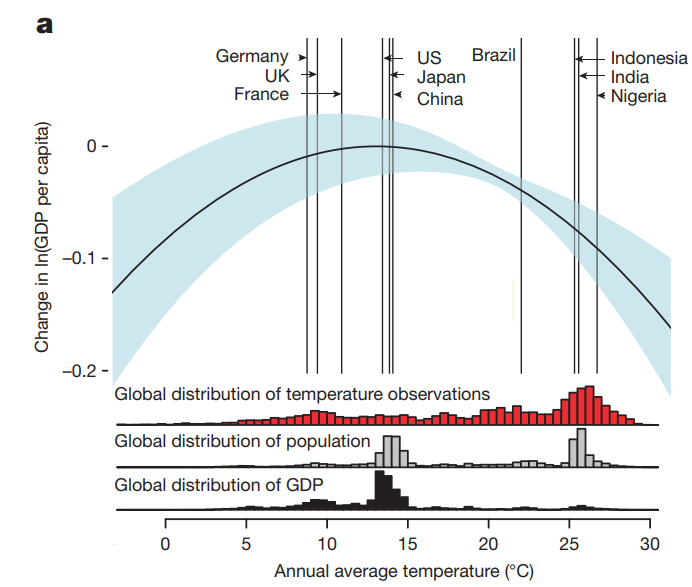

The first reason is the geographical position. Burke et al. (2015) showed that economic production is related to temperature in a non-linear relationship (Figure 1) and that the optimum is reached for countries that have an average annual temperature of 13°C.

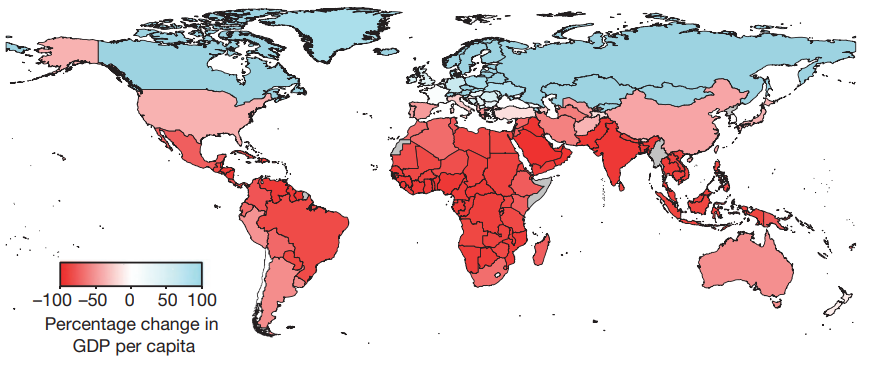

Climate change has already pushed average temperatures upwards, and this trend will continue in the future. This means that the further countries move away from the optimum temperature of 13°C, the more their GDP will decrease, and that the decrease will be more significant for more extreme temperatures (going from an average of 15 to 16°C has less impact than going from an average of 20 to 21). As a consequence, in Figure 2 we can see the different effects that an increase in temperature of 1°C will have on countries’ GDP depending on their geographic location. African, South Asian and South American countries will be the most targeted.

Another key element is the economic structure of the countries. Agriculture is one of the sectors that climate change will directly affect. The rural income of farmers will decline and the costs of food will rise, negatively impacting poorer households and increasing inequality. This means that within the same country, the poor will become even poorer. This will be particularly relevant for LDCs (Least Developed Countries), as they often have a high share of employment in the agricultural sector and a larger share of income dedicated to food consumption. The same article by Paglialunga et al. (2020) shows that “countries characterized by higher level of income inequality […] are also the most vulnerable to climate change”. These aspects highlight the interconnection between cross-country inequalities and within-country inequalities, and how they feed into each another in a vicious cycle.

Within-country inequality

Climate change will not only disproportionately affect different countries, but also different groups of people within the same country. We refer to this phenomenon as within-country inequality and it can depend on demographic characteristics (age, race, religion, etc.), assets and income and access to public resources. Within-country inequality has yet to be fully explored. However, an important paper by the United Nations was able to map the characteristics of this type of climate inequality.

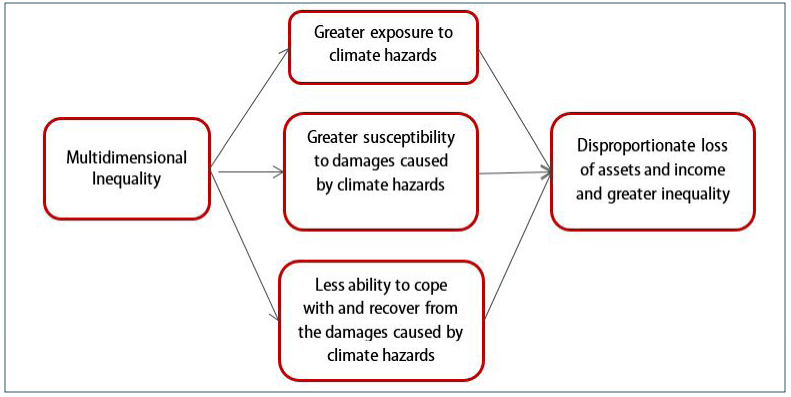

The issue develops in several areas (Figure 3). The first channel concerns the greater exposure to climate hazards. Especially in developing regions, people with low income live in coastal areas prone to flooding or are generally located in areas more prone to natural hazards where housing prices are lower. In rural areas, where a larger share of people lives below the poverty line, people are more exposed to drought. In these cases the situation can be so critical that people are forced to leave their homes, giving rise to climate migration phenomena.

Politics also plays a significant role. The Power Weighted Social Decision Rule (PWSDR) states that in an unequal society, when political decisions are made, the utility of the advantaged (read: powerful) groups outweighs the utility of other members of society. One example is the disaster of Hurricane Katrina, which mainly affected the black community of New Orleans. Discriminatory housing policies led to a concentration of black people in vulnerable areas, to the point that “a black homeowner in New Orleans was more than three times as likely to have been flooded as a white homeowner”.

The second sphere relates to the susceptibility to damages. This means that even if people are exposed to the same climate hazard, some groups suffer more damage than others. A trivial example is that in a heatwave, people who can afford air conditioning will fare much better than people who cannot. The more fragile categories, such as the young and the elderly, face much bigger risks when involved in climate disasters.

Other types of inequality, like gender inequality, can be crucial. For example, in developing countries women often have the task of collecting water and firewood and have to travel long distances. Climate change will further worsen their conditions. Racial and ethnic inequalities are particularly important, as low-income status is often related to these factors. Finally, drought or floods can cause an increase in market prices, especially for food. This has a much greater impact on the poorest households that usually spend most of their income on basic needs.

The last sphere is the ability to cope and recover. Some social groups don’t have the monetary resources necessary to recover from the damages of climate change. In these cases they enter a cycle that exacerbates their condition of inequality. For the same reason they often don’t have insurance. Problems persist if we consider public resources, as there can be discrimination in access. The Power Weighted Social Decision Rule is an example of this dynamic.

Why it’s also our problem

Inequality is a huge problem for society. In addition to being morally unacceptable, it actually harms not only those who are directly affected by it, but the entire population. Inequality favors crime, depresses the economy, and deteriorates social stability. Especially in the interconnected world we live in today, it’s impossible to think that we can efficiently tackle climate change by leaving people behind. At the political level, we need to create policies at national and international level to mitigate these disparities. As a society we need to raise awareness about the unequal effects of climate change, knowing that the issue is very complex and has multiple roots.

Cover image by Meridith Kohut for The New York Times.