In 2008, Timothy Morton coined the concept of Hyperobject to refer to all types of phenomena or objects whose spatial and temporal dimensions, combined with the plurality of forms in which it manifests itself, make it not directly experienceable as a concrete uniqueness. The climate crisis is the Hyperobject par excellence:

“I cannot see it. I cannot touch it.

But I know it exists and I know I am part of it.

I should care about it”[1].

~ Timothy Morton

Indeed, we can see and touch droughts, we can calculate the loss of biodiversity, we can measure the rise of the sea and the melting of ice: we can only experience all the effects and phenomena caused by global warming, but we cannot see it directly. The climate crisis affects all human beings closely, it is connected to all our activities and the objects we deal with, yet it is perceived as distant and all too often climate inaction is an everyday occurrence. We must take care of these real, concrete objects, immense in time and space, we must move our consciousness to ecological thinking. The solution to bring this change within society lies with the social actors, the protagonists of the cognitive, social, environmental and economic revolution. Their purpose is driven by the need to create positive changes of fundamental importance for societies enhancing citizens’ wellbeing. That’s why we decided to have a talk with Sfridoo (private company), Prato municipality (public sector) and WWF Italy (NGO).

Innovation, industrial design, and the capacity to reimagine value chains are among the most important means for the private sector to foster a paradigm change in production. Indeed, Sfridoo represents a good added value to this purpose trying to reshape the waste management industry in Italy. Founded in 2017 by Marco Battaglia, Mario Lazzaroni and Andrea Cavagna, three innovative architects from Bologna, Italy, Sfridoo is redefining the way we think about waste and surplus materials produced during construction and demolition activities.

What sets Sfridoo apart is their physical marketplace (and in the following months also online with a new platform) that promotes circularity and facilitates a shift in the way waste is perceived. During the chat that we had with Andrea, he described their activity as “facilitators,” providing waste management and circularity consultancy to reduce companies’ environmental impact and connect different sectors by redirecting waste from one economic actor to another who is going to use it as raw production input. Textile, construction, luxury, agri-food, manufacturing, and chemical are only few of the sectors they work with, achieving over 300 “matches” between corporations and reducing up to 95% of companies’ waste in some cases. Impressive, right?

Of course, there are challenges in this industry. The Italian normative on waste and raw materials can be a limiting factor, and material and chemical analysis can be tricky. However, Sfridoo counts on different partners and labs to help them analyze materials and understand how to better advise producers so that their waste may be more functional to other actors. Sfridoo‘s environmental but also social impact is huge, closing economic circles, avoiding the input of new materials in production, therefore saving precious resources, and educating people and corporations.

Knowledge of the territory, analysis of the local productive structures and the capacity to listen to the citizenry helps local administrations of Prato to promote green urban development. The latter is a Tuscany city famous for its textile industrial district that has its root in the Middle Ages. Prato has been selected by the EU Commission as one of the 100 cities in Europe aiming at becoming carbon neutral and tech-smart by 2030, being one of the seven carbon-neutral aiming cities in Italy, and the only non-metropolitan city among them. The Next Generation Prato is the biggest outcome of Prato Circular City.

How is Prato pursuing such an ambitious goal? Leonardo Borsacchi, scientific manager of Prato Circular City detailed described us the City’s strategy. Knowledge of the city’s territory, analysis of local productive structures, and capacity to listen to its citizenry have enabled the municipality to promote circular production, consumption, and an efficient use of urban resources. When it comes to citizens’ attitudes towards sustainability, they are generally more attentive to environmental than social and economic impacts. However, there is a growing interest in sustainability overall, and Prato is no exception. The city also has a large civic engagement thanks to associationism, which helps to understand local necessities and difficulties.

One of the secrets to Prato’s success is its rich textile tradition, which dates back decades. Textile workers in Prato, known as “cenciaioli,” were masters at assessing the type of garment by touch alone, enabling them to recycle materials. Today, circularity also encompasses water use in the textile district, where a special treatment plant purifies and reuses wastewater in production. However, as with most sustainable development initiatives, the normative barriers can make things difficult.

Lastly, the third sector, with NGOs , can play a big supporting role, based on values, free from profit-maximizing objectives, valuable to direct the vision of other actors of our society and to educate companies and organizations to sustainability. That’s why we decided to talk to WWF Italy, in particular with the Head of Sustainability Office of the conservation department Eva Alessi and the manager of the Business and Industries Office Giuliana Improta to understand WWF Italy’s key role in achieving environmental sustainability and biodiversity protection.

The red yarn used by WWF Italy to choose how to tackle environmental impact is based on identifying which of the biggest markets and leader industries are environmentally more in danger. This follows its overarching criteria of selection, which is based on believing in the contribution that each company can give to their cause, considering also reputational aspects, quality and features of products (and services) offered by corporations. Furthermore, they give a deeper look into companies’ history and every aspects of their products offer to better assess if a potential collaboration would be in line with WWF Italy core values.

Science-based targets, divided by sectors, are used as guidelines to evaluate how to efficiently implement GHG emission reduction plans because “this is a unique, particular, approach, designed to create a sustainable path which is credible, solid, measurable and replicable” Eva added. In a word: Holistic. Furthermore, to take care and tackle the food waste through the campaign “Food4Future” programme, they are involved in ending agri-food waste, closing water and chemicals loops, spreading circularity with through their collaborations. Mulino Bianco, through its “La Carta del Mulino”, is an example of successful partnership in agrobusiness. It represents a list of 10 rules, agricultural companies need to follow with the aim to make the soft wheat cultivation chain more environmentally sustainable, giving back space to nature on farms, promoting natural soil fertility, reducing the use of synthetic chemicals in the production chain and reducing the risk of pollution. Another important example of collaboration is represented by Bolton Food (Rio Mare, Sapiquet, Isabel). Indeed, WWF Italy create a partnership to promote more sustainable fisheries and strengthen advocacy efforts for responsible tuna stock management globally, promoting and reaching a sustainable value chain, while granting traceability and transparency.

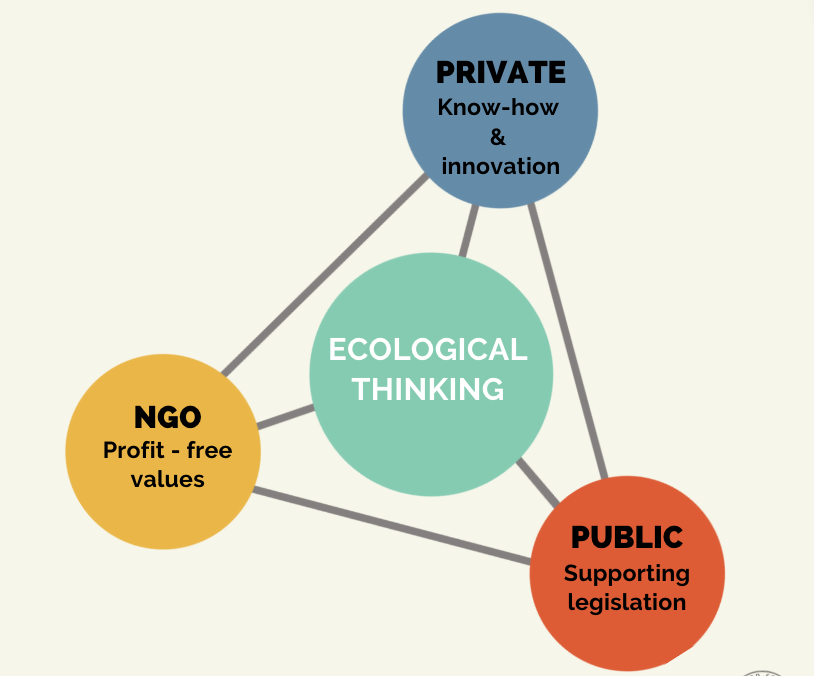

Companies can solve problems that the public sector is not able to face, also because of the lack of specific and supportive legislation. Public administrations know the territory, its actors and the needs of the citizenry, but they need the private know-how in order to enable their policies. Not-for-profit actors can drive private companies’ change and guide their sustainability’s strategies, integrating socioenvironmental concerns in their economic activities. These are a few example of the interlinked relationships that the public, private and third sectors entertain, making sustainable development a feasible ambition. Although these actors function in different ways, cooperation and collaboration are the biggest tools they have to create and implement a real and efficient action, thanks to dialogue and understanding of each other’s needs.

Hyperobjects require ecological thinking. Systemic problems require systemic solutions. Climate change is one of them and these social actors have the potential to influence society fostering a systemic change, thanks to the different perspectives and knowledge they bring in. In conclusion, companies, public actors and NGOs moved by the same vision will be crucial to deliver a powerful action.

[1] https://www.hcn.org/issues/47.1/introducing-the-idea-of-hyperobjects