Since it was released on Netflix last December, Don’t Look Up has been at the top of the platform’s most viewed titles. Adam McKay’s new movie portrays the fictional story of two astronomers and their desperate attempts to warn humanity of a comet’s impending impact with Earth. The calculations have been made many times, the data are objective: this catastrophic event will cause the extinction of the entire planet in six months.

Of course, we don’t want to get into a technical discussion about the quality of the movie (that’s a job for film critics), but we want to analyse its content and message. The plot is in fact a not-so-subtle metaphor of climate change and how humanity is dealing with this major issue.

Don’t Look Up portrays a cynical satire of modern society and its attitude towards climate change. The feeling that dominates the film is frustration: an objective and tragic catastrophe, which should be received with fear and a willingness to act, is manipulated and questioned. The truth is taken, distorted, and bent in favour of individual interests, be they economic or political. The public, distracted by other issues (often insignificant, for example the engagement of a famous pop star) and confused by different opinions, follow ideologies that are not necessarily supported by facts.

The movie develops its argument on several levels.

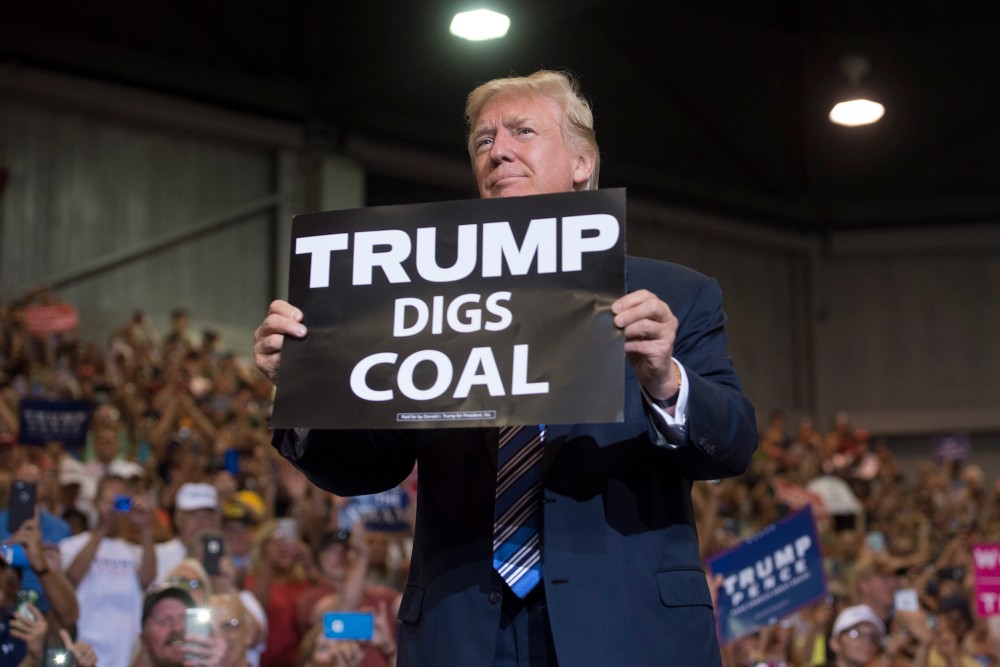

First, there is the political dimension: the President of the United States, played by Meryl Streep, decides to delay and ignore the issue just to maintain political consensus, but she is ready to act as soon as it could further her cause. “Don’t look up” then becomes the anthem of a political alignment that exploits the division of the public, ignoring scientific facts. How can an entire government be able to publicly support ideas that contradict scientific truth? We don’t have to go much back in time if we think of the United States’ withdrawal from the Paris Agreement promoted by the Trump presidency (who also called climate change “a hoax”), a decision that was harshly criticised by the international scientific community.

The same event is linked to the theme of the economic interest, which in the film is portrayed through the figure of the technological guru, clearly inspired by some of the most iconic characters of the Silicon Valley, such as Steve Jobs and Elon Musk. Once the comet is proven to be composed of precious minerals, safety and survival are put at risk in order to pursue economic gain, with the complacency of politics. And this is how a campaign in favour of the comet begins in the movie, and it is portrayed as an opportunity for economic growth and job creation.

In his press conference on June 1, 2017, Trump outlined his reasons for leaving the Paris Agreement, mentioning job losses and negative impacts on the economy (claims that turned out to be either false or exaggerated). The support shown to the fossil fuel industry was clearly motivated by economic and political reasons and contrary to any scientific truth, even at the cost of ignoring the risks to human health and the environment.

Leaving aside the political sphere, there are countless examples among companies in which profit takes precedence over the common good. One of the first examples that popped into my mind was the case of the Volkswagen emissions scandal in 2015, when the famous German carmaker was accused of installing a defeat device that was used to cheat emission tests. The firm has been accused of manipulating approximately 11 million cars around the world. Another case comes from my country, Italy, where the ILVA plant in Taranto (today Acciaierie d’Italia), one of the largest steel plants in Europe, devastated the area with pollution, causing more than 11 thousand deaths in eight years. Unfortunately, the examples could go on for pages.

The third main actor of Don’t Look Up is us, the citizens. In the film, the general public appears divided between those who believe and fear the threat and those who remain sceptical or simply disinterested. The reference to the situation of the pandemic is immediate, but the same mechanism has been repeated for decades with climate change.

It’s been a long time since scientists started warning us about the effects of pollution and climate change. An example is this 1958 excerpt from The Bell System Science Series, a series of popular science television specials, where Dr. Frank Baxter clearly describes the dangerous effects of climate change, from melting ice to rising sea levels. However, even though the problem was already known, it took decades before serious action was taken, and even now that we are fighting against time we are far from doing everything we can to stop climate change.

Today almost the entire population acknowledges the existence of climate change, but the denial is still present in more subtle forms. The problem is above all the tendency to avoid or minimize. Some of the most common denial arguments concern the influence of human activity (climate change is cyclical and has already happened in the past); on the opposite side there is the so-called “doomerism” approach, which states that climate change is now too advanced for human intervention; others believe in climate change but think the consequences won’t be so extreme as they want us to believe.

This attitude is perfectly shown when in Don’t Look Up the astronomer Kate Dibiasky, in a fit of anger and despair, announces the news of the impending catastrophe and becomes a meme. A clear parallel to the treatment given to Greta Thunberg after the speech at the United Nations Climate Action Summit on September 2019.

Closely connected to the public is the role of the information system. The media are capable of heavily influencing the audience, but at the same time they feed on public attention: in an endless cycle, the news that are prioritized are often superficial but popular, while the most pressing issues are ignored. This is until the menace becomes more real and the debate more inflamed. Then social networks become the arena of two opposing factions, favouring an infodemic in which fake news, rumours and opinions unsupported by facts spread more and more easily. A situation that feels similar to what we had to face in the acute phases of diffusion of COVID-19.

Overall, the movie does not provide particularly original insights to the debate on climate change, as the interference of politics, economics and public opinion were already known. The merit of Don’t Look Up is to make the audience uncomfortable for the grotesque reality that we are living in, where humanity is not even able to collaborate and make the necessary effort to preserve its own existence. And the final line of the film feels like a prophecy we hope it will never come true: “We really did have it all and we didn’t know it.”