How humans cope with Climate Change.

Since when the “Green New Deal” has been inserted in the political agenda across many countries, the coverage of Climate Change in mass media suddenly surged. The main facet that is outlined is one of a threatening, disruptive, unavoidable phenomena.

While these characteristics are supported by scientific evidence, this same tendency of depicting Climate Change as dramatically irreversible produces two major backslashes, both restricting the general public’s participation and polarizing policymakers (scientific supported) opinions and will.

Dan Kahan, Professor and theorist of Cultural Cognition at Yale University gave a major contribution to the understanding of these phenomena, that we will explain by introducing Kahneman’s “Two Systems of Thought” and Maslow’s “Hierarchy of Needs”. Each of these representations marginally explains both the behaviour of the general public, as well as that of the scientific accustomed public who is familiar with scientific literature.

After an explanation of both typical behaviours, we will end the discussion by posing an alternative approach to encompass and promote action within these two social groups.

Let’s start with the general public. Kahneman’s research on Behavioural Economics divided the human reasoning process into “Slow” and “Fast” thinking. His thesis poses a dichotomy between two models: “System 1” is fast, inactive and emotional, “System 2” is slower and more logical. By using “System 1” of thinking, people will eventually run into biases that might distort how risk is perceived, lowering, in this case, the chances of personal liabilities to occur. Nuclear waste disposal stocked underground that might pollute aquifers, as well as eutrophication of aquatic ecosystems will be regarded and processed by “System 1” as long as they are not imposing immediate threats to the general public. Spillover, the phenomena described by David Quammen in 2014 that could lead to a pandemic is a good example of both the behaviour of the general public, as well as that of policymakers in the case of Covid-19.

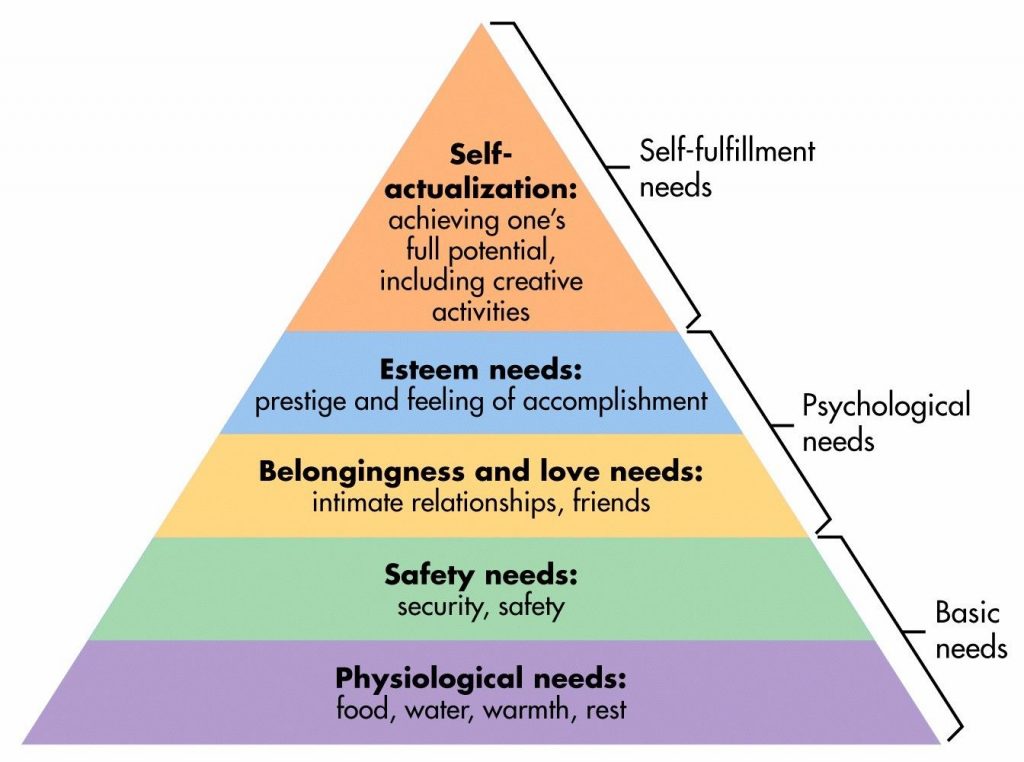

This phenomenon is coupled and amplified by Maslow’s “Hierarchy of Needs”.

From the bottom to the top, these are the prerogatives that humans must satisfy in order to be fulfilled. This theory fully explains why the general public isn’t, and shouldn’t be blamed, actively concerned about the Climate Crisis. While the threats posed are indeed unavoidable and dramatically damaging, they still look distant from daily consequences. Instead, most humans currently suffer unemployment, unfulfillment, depression, poverty, illiteracy, hunger. Climate activists as Leonardo di Caprio are indeed virtuous in their actions, but cannot be seen as a term of comparison, they already reached the fulfilment of basic needs that most of the population is still looking at.

As most of the consequences of the Climate Crisis, this will only get worse as the threshold of 1.5 degrees will be exceeded.

Yet, this doesn’t explain why there is still a debate among policymakers and scholars on Climate Change. While it might be justifiable that common people do not actively look at solutions, why don’t politics offer a concrete answer? Kahan’s studies offer a hypothesis in this regard.

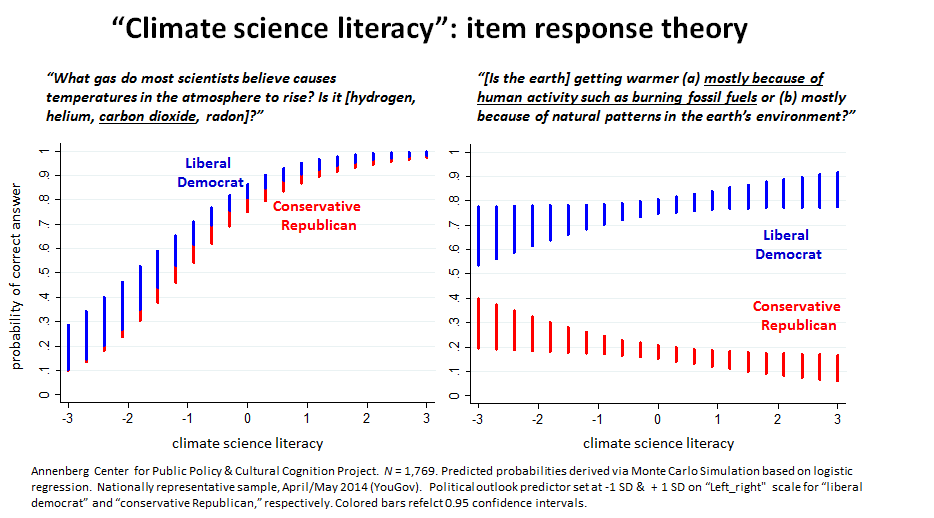

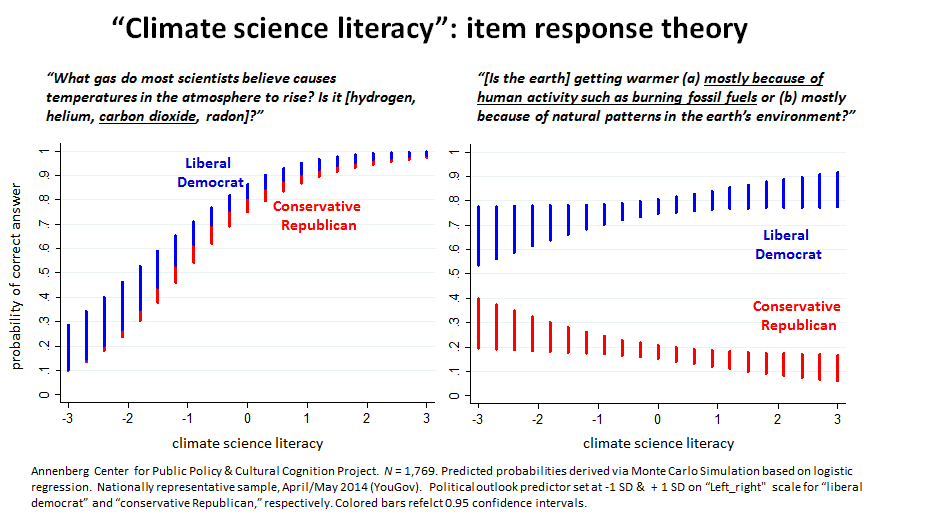

Drafted on a random sample of 1769 individuals that identified themselves as literate Liberals or literate Conservatives in the USA, the result of the study shown a surprising result. Scientific evidence, rather than converging opinion drives people to anchor to their previous beliefs, polarizing the outcome and exacerbating the debate. This theory is supported by Kahneman’s framework, showing that individuals with high literacy background are using scientific facts as an anchor to support their thesis. Those who have an interest in denying Climate Change, even looking at scientific facts, will find counter-facts to maintain their comfort zone, the study says. This might happen for shareholders in the fossil fuel industry, as well as for all those people who might lose their job during the Green New Deal transition, as proposed by AOC.

In this light, this might be why in Europe the Green New Deal is being narrated more proactively focusing on business opportunities rather than on catastrophic risk. While this certainly is an effective strategy to call for action several classes of shareholders, the risk component must not be taken out from the equation for an effective response.

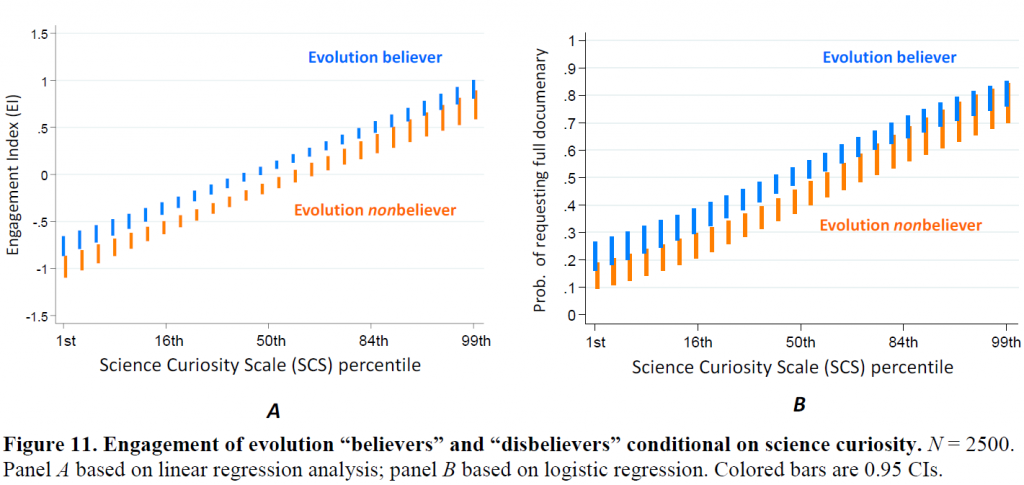

Another key aspect for coping with the Climate Crisis is promoting scientific curiosity to reduce polarization and draw attention to the topic.

Kahan shows that scientific curiosity is an effective antidote to ideological polarization, as shown in the graph. Curiosity leads to questioning prior beliefs, producing a converging outcome across opposite political factions. In this regard, educating on critical thinking rather than climate notionism, might be an effective solution for involving both ideological groups.

While this might be a partial antidote for educating future policymakers, what about the general public? Here resides the most challenging aspect of coping with the Climate Crisis. Inaction cannot be blamed where more prominent needs are still present in the everyday life of most citizens. Slacktivism is much more of a problem for those who benefit of privileged conditions.

For those who are in need, the focus must be searched somewhere else: in a household, clean water, sufficient food, public healthcare, assistance on depression, self-fulfillment.

For a healthy world, we need healthy humans.

Further Studies:

- Kahan D, “The polarizing impact of science literacy and numeracy on perceived climate change risks” (2012) https://www.nature.com/articles/nclimate1547

- Kahan D, “Climate-Science Communication and the Measurement Problem” (2014) https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2459057

- Kahan D, “Motivated Numeracy and Enlightened Self-Government” (2017) https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2319992