I’m sure that in primary school, during history class, pretty much anyone has heard teachers talking about the almost-phantasmagorical world of dinosaurs. Most millennials, who grew up with dinosaur-themed cartoons like The Land Before Time, found themselves confronted with the news that the prehistoric creatures had been extinct for millions of years.

But what exactly does the extinction of a species entail? Are there ways to monitor the life of animal and plant populations? And, most importantly: what can we do to protect our ecosystem and prevent, or delay, species extinction?

On an international level, a non-governmental organisation called IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature) deals with the conservation of species and of their natural environment. The organisation is tasked with compiling a Red List of endangered species, with the aim of raising public and governmental awareness of species conservation.

The first Red List was published in 1948 and it is considered, to date, the largest database of information on the conservation status of animal and plant species around the globe.

The database is possibly the most authoritative and objective system for classifying species at risk of extinction. It’s mainly used as a classification tool within the context of international programmes and agreements, but it can also be used to develop strategies that can safeguard ecosystems at different levels of governance.

What are the main criteria used to determine the degree of extinction risk?

In order to determine the degree of extinction threat of a certain species, the IUCN uses data provided by zoology and botany experts.

At present, five are the criteria that a species should tick to be assigned to a Red List category:

A – Declining population

This concerns the rate of decline in population of a specific species, regardless of its initial numerical size. For a species to be included in the lowest-threat category (“Vulnerable”) its decline in population must be greater than 30%, over a period of 10 years or three generations, whereas to be included in the highest-threat category (“Critically Endangered”) its decline must be greater than 80%, over the same period of time.

B – Small Distribution and Decline or Fluctuation

The second criteria focuses on the size of the geographical area of distribution of the species. To be considered at risk, this area must be less than 20 000 km2 big and deteriorating (IUCN defines Habitat degradation as a decline in habitat quality for a species, related to changes in food availability, cover or climate.).

C – Small Population Size and Decline

This criterion is similar to the one above, but it is applied to populations of less than 10,000 individuals.

D – Very Small or Restricted Population

Criterion D only applies to species with less than 1,000 individuals and an extremely small range of distribution (less than 20 km2).

E – Quantitative Analysis

Quantitative analysis is based on estimated quantitative extinction probabilities for an exact time interval. According to this criterion, a species can be defined as:

– Vulnerable (VU): where its extinction probability is estimated to exceed 10% over 100 years;

– In danger (EN): where it exceeds more than 20% in five generations;

– Critically endangered (CR): where it exceeds more than 50% in three generations.

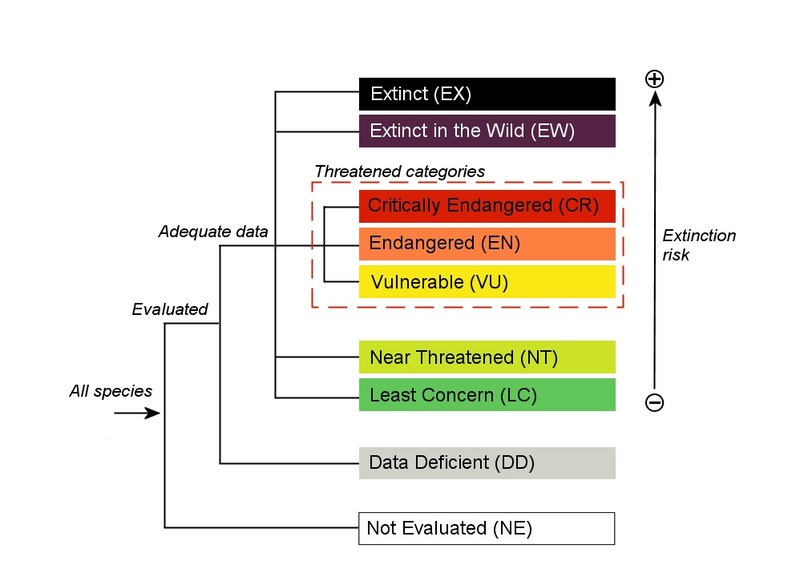

Once all parameters have been taken into account, each species is assigned to one of the 11 categories that describe its conservation status.

EX = The death of the last specimen of the species has been ascertained.

EW = The species is extinct in nature and exists only in captivity.

LC = no risk of extinction in the short/medium term.

Then, the three categories at risk can be analysed:

CR = The population of the species has decreased by 90% in 10 years; or its distribution range has fallen below 100 km2; or the number of individuals is less than 250.

EN = The population of the species has plummeted by 70% in ten years; or its distribution range has fallen below 5000 km2; or the number of fertile individuals is less than 2,500.

VU= The population of the species has decreased by 50% in ten years; or its distribution range has fallen below 20,000 km2; or the number of fertile individuals below 10,000.

Finally, the last categories concern those species whose degree of threat is relatively low or non-existent such as horses, cats, dogs etc.

How can we save species from extinction?

Currently, according to the IUCN Red List, around 160,000 species are at risk of extinction, but there’s a high chance that this number could rise – especially if we consider the most remote and inaccessible areas of distribution, like the deep sea.

At first, thinking of such large numbers could make us feel helpless. We must, however, always think of our behaviour as a small drop in a large sea, made of hope and love for Mother Nature. Hence, let’s look at some of the behaviours we can adopt in our daily life to preserve nature!

- Be aware of plastic garbage

How many times have you found unpleasant plastic bags floating next to you while swimming? Well, those bags are often ingested by turtles, who mistake them for jellyfish. Furthermore, sea garbage, in addition to killing a large number of fish that inhabit the seas, it’s also been found to have serious effects on the health of those humans eating fish

2. Shop consciously

Several foods and goods available on the market are made from materials that affect animals and damage their habitat in many ways. For instance, there are brands of coffee or fair-trade chocolate whose production does not result in the deforestation of rainforests or the destruction of habitats. Picking those is a good example of conscious shopping.

3. Volunteering for the environment

Be yourself an integral part of the change. Why not join a local, national or global conservation organisation? – think of Legambiente, LIPU, etc. Or, alternatively, you could “adopt” an animal through these organisations (this could be an unusual, but original birthday present).

To learn more about the topic, please consult:

https://www.doc.govt.nz/documents/science-and-technical/TSOP22.pdf

https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2019/05/nature-decline-unprecedented-report/