Part one – The effect of loss-aversion in the hesitancy of changing food habits

Peter is an 18-year-old boy in his first year of university. From an early age, he has always been used to eating meat five times a week. Peter is very satisfied when he eats it and, for this reason, he continues to buy and consume the same kind of meal even now that he lives alone.

For some time now, however, Peter feels tired and noticed he gained weight. He also had blood tests whose results showed high levels of cholesterol. Talking to himself, he thinks he should go on a diet, yet he does not feel he has the right motivation to change. Later on, he decides to talk to Kate and Hugo, two colleagues of him who have been vegetarians for a few years. Peter listens carefully to the motivation that led his peers to radically change lifestyle; nonetheless, he rejects the offer to try eating plant-based food for a week.

Is there a deeper reason behind Peter’s categorical rejection? Or rather, is it possible to explain the difficulty of changing those habits that prove harmful to our health through the application of behavioural economics?

The answer lies in the cognitive theories of Kahneman and Tversky, whose contribution to economics through the Prospect Theory won the Nobel Prize in 2002. In the Seventies, the Israeli psychologist Daniel Kahneman and his colleague Amos Tversky wondered how decision-making processes change when facing with risk decisions. They came to the first discovery following the administration of questionnaires to students and specialists: according to them, people deduce conclusions based on statistical samples that are not representative of the universe, as they tend to confuse a small portion of a phenomenon with the whole. Hence, the difficulty in computing the expected probabilities of an event.

However, it is with the prospect theory, published in Econometrics in 1979, that the two authors gained the most resonance among economists of the time.

They show how individuals, even when faced with problems of great simplicity, often disregard with their behaviour even the fundamental axioms that guide rational choice.

The model is purely descriptive of what happens at a behavioural level when making a choice; that is, they do not claim that one should behave according to the model. The aim they proposed was to identify “how” people actually make decisions, in order to detect mechanisms that would account for that behaviour and allow for its prediction.

The paper begins by criticising the theory of expected utility and, using the world of betting as demonstration example, proposes a different model: the alternatives are evaluated through a value function that consider variations in wealth.

This means that people tend to weigh the two events separately; however, what is even more noteworthy is that they give much less importance to gain than to loss, which explains the peculiar characteristic of the value function of being asymmetrical.

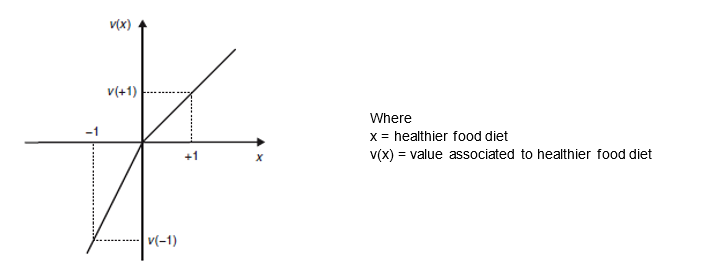

The left side of the function refers to losses and is represented with a relatively steep convex curve; the right part refers to gains which can be depicted by a smoother concave curve.

The differentiated trend of the two functions produces notable effects for the purposes of forecasting the actual behaviour of choice of individuals.

In fact, the asymmetricity of the function explains how often individuals face with a possibility of choice, reject combinations of events which, added together, would bring them greater wealth.

The preference for choice alternatives can change according to the personal status quo, which represents the level of reference that leads the consumer to turn towards a type of good. When the decision is made consecutively, habitual behaviour is triggered. Conceiving the consumer’s eating habits as the status quo, certain behaviours can be explained through reference effects.

In order to understand if and under what conditions a consumer is willing to give up his or her status quo, Cramer performs an experiment with the aim of testing the assumption according to which endowment effect is stronger for hedonic good rather than utilitarian good.

Among the various parameters considered, those concerning the utility of the product (healthiness, gives energy, not fattening) show the tendency towards utilitarian goods; in this case, there is a greater probability among consumers of being willing to change a hedonic for a utilitarian good.

On the contrary, on average people prefer to remain under the current state of affairs when other variables such as “hedonism”, “taste”, “appearance” are considered.

The prospectus theory allows to provide a more analytical explanation of Peter’s reluctance to change food habits.

The third quadrant represents the subjective value that Peter attributes to the healthier diet, while the first one shows the value associated with the diet to which he is accustomed. Although a change in eating habits would benefit Peter’s health, he paradoxically associates less value to a healthier food than his current condition. Mathematically, |v(-1)| > |v(+1)| , that is, the gain representing a healthier diet is smaller than (the absolute value of the) loss of the current habit. Therefore, the net effect will be negative, which explains the reluctance of the subject to change the current state of affairs.

In the next article we will see how social media and marketing strategies influence people’s food choices.